There are no winners in the Depp/Heard trial – but we all lose

Trial by TikTok risks setting the gender justice movement back decades

Hello, and welcome to this weekly free newsletter from The Flock with Jennifer Crichton – this week with a very special guest writer. Just a reminder that you can support the work that goes into this newsletter, and access all manner of extra columns, interviews, audio content and conversation throughout the week, by becoming a paid subscriber.

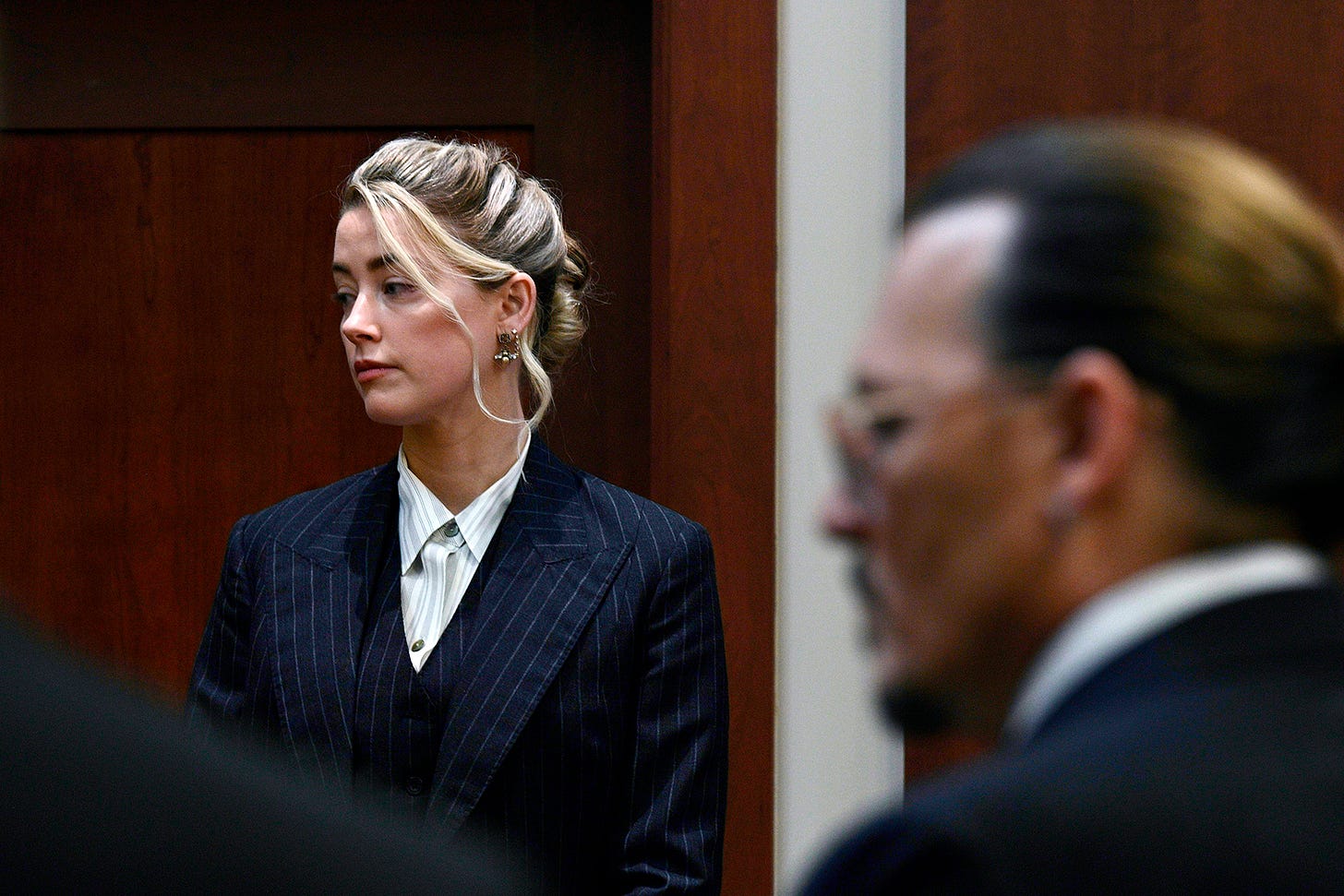

On Friday, the jurors in the Depp/Heard defamation trial were sent away for the Memorial Day weekend, ordered to set aside the trauma of the world’s highest profile court case to engage instead in sausage sizzling and celebration. When they return to deliberate on Tuesday, the fate of two household names will rest in the balance – but there’s far more than reputation and $100million at stake.

Over the last six weeks, as the world has watched events unfold from a nondescript courtroom in Fairfax, Virginia, clipping the most controversial morsels to repeat for effect on TikTok, survivors of domestic abuse, coercive control and gendered violence have struggled. The testimony has been triggering. The witch hunt unsettling. The victim-blaming all too real.

I know many women who have tried to avoid the coverage as much as possible. I’ve personally unfollowed dozens of people on social media, switched off the news coverage, avoided the headlines. Still, the trial has followed us all around the Internet, making the progress of Me Too feel ever more fragile. I didn’t feel equipped to write about it. But I also didn’t feel I could ignore it any longer.

Which is why today, I’m handing over the newsletter reins to domestic abuse specialist, and survivor, Evie Muir. With ten-years experience supporting survivors with intersecting experiences of gendered and racialised trauma, Evie is perfectly placed to explain why this trial has been so triggering – and how, no matter the outcome, it risks setting the movement for gendered justice back decades...

This week, I left a group chat I’ve been part of for over ten years, a home to friendships shared for almost three decades. Turning my back on particular individuals within it came effortlessly – I’ve accepted that they are no longer safe for me, a Black, queer domestic abuse survivor. The signs, of course, had been there for a while, but a history of shared childhood memories could no longer glue us together amidst the differing ideological beliefs that tore us apart. Ultimately, it was the Depp/Heard trial that proved the final straw.

The break came after I watched a 24-hour campaign of hate unfold. With each message that flashed onto my screen, it became clear that the trial, viewed through the lens of entertainment, was not something of genuine interest or concern, nor something to learn from or interrogate. Instead, speculation and gossip informed by a deluge of TikToks and memes was followed by laughing faces and unrelentless victim blaming. As I read through the chat, I felt the familiar sensation of being triggered. My stomach churned, my heart raced and my breath quickened. A panic attack rose slowly through my body, culminating as I stared at the final message: “It’s her own fault, isn’t it”, it read.

Reading this exchange, I was transported back to a place of unsafety, instinctively knowing that this group was not safe for me to disclose my own experiences of abuse to. While my initial trauma response was to remove myself from the chat immediately, I decided to instead practice the abolitionist act of ‘courageous conversation’. Acknowledging that I couldn’t expect anyone to uphold my boundaries if I didn’t communicate them, I reminded the chat to be conscious of what they were posting, that they didn’t know who would be impacted. Johnny Depp and Amber Heard wouldn’t see what they said, I reasoned, but the survivors around them would. My message gained four likes. I received one phone call and one direct message of support. No one replied in the chat, and those who had been posting the harmful messages didn’t respond or apologise.

Two days later, another TikTok video mocking Heard was posted, and another stream of laughing emojis followed in reply. Prickled with the recognition that these friends of over two decades had made a conscious decision to not respect my boundaries, I removed myself from the group.

Whilst possibly the most hurtful, this isn’t the first harmful interaction I’ve been subjected to during the duration of the trial. As a domestic abuse survivor, practitioner and advocate who speaks openly on the issue, I’ve felt like an open target for people to expunge their verbal diarrhoea of uninformed vitriol. Always open to conversations that inspire reflection, I’ve instead been pounced upon by those whose eyes glisten with the joy of playing ‘devil’s advocate’. One acquaintance even left me a series of unsolicited voice notes ranting about his disgust for women.

This is the reality that domestic abuse survivors have been navigating throughout this trial. Regardless of the verdict, survivors like myself have been reminded just how unsafe our immediate circles are, not to mention wider society. The overwhelming solidarity which poured from all directions after Sarah Everard’s murder is now nothing more than outdated allyship, washed away by the first wave of celebrity scandal. We’re reminded that misogyny is far from eradicated. Rather, it’s been insidiously preserved for the moment a friend, family member or favourite pirate-playing actor gets accused of abuse. All that we are left with is a diminished network of support and a deepened fear of services – who can we trust to help us?

What’s most disappointing is the wasted opportunity for tangible change at both the systemic and individual level. This trial held the potential to challenge and deconstruct many formerly unquestioned beliefs and, in doing so, dismantle structures of oppression. Instead, these systems have been reinforced.

The corruption and injustice at the heart of the criminal justice system, for example, could have been exposed. Evidence already tells us it’s not fit for purpose. This trial could have raised awareness of the ways that abusers trap their victims for longer, using defamation suits and Non-Disclosure Agreements (NDAs) to manipulate the narrative and silence their targets. It could have highlighted the fact that, while such approaches may be more commonly used by the wealthy, the weaponising of the criminal justice system plays out time and time again through criminal, civil and family courts too. Such behaviour is now so common, it has been condemned within the Domestic Abuse Bill, which now prohibits perpetrators of abuse from cross-examining their victims in person, creates a statutory presumption that victims of domestic abuse are eligible for special measures in the courts, and has protections in place for when family proceedings risk further traumatising victims.

Rather than platforming these inequalities, however, the mass TikTokification of this trial has signalled to abusers how easy it is for them to weaponise the system. We’re already seeing an increased number of perpetrators using the state as a tool of harm, with Marilyn Manson since filing a defamation suit against Evan Rachel Wood, who accused him of sexual abuse.

In taking this approach, we have lost an opportunity to deepen our understanding of abuse – that it’s rarely just physical, that integral to it is an enforcing of power, control, oppression and exploitation. There’s a helpful acronym, ‘DARVO’, that can be used to understand the insidious ways perpetrators use gaslighting as a form of emotional abuse to evade accountability. It defines how abusers Deny the accusations made against them, how they Attack the character – in particular the mental health – of the person accusing them, causing more physical, emotional and material harm to them in the process, and how they Reverse the narrative of Victim/Offender. One way this is achieved is by carelessly throwing terms like ‘mutual abuse’ into the mix.

‘Mutual abuse’ has long been discredited as a myth by domestic abuse experts as being an invalid and misleading defence that plays into the stereotype of the ‘ideal victim’: where only white, cisgender, heterosexual women who are passive and weak, who don’t fight back or try to defend themselves, can be victimised. Entertaining the term ignores the ways that power and control are integral to abuse, allowing perpetrators to play the victim. It’s equally important to recognise that cases dismissed as ‘mutual abuse’ disproportionately impact Black survivors – so often stereotyped as being ‘angry’, ‘strong’ and ‘independent’ and therefore less vulnerable – and survivors in LGBT+ relationships, due to them not fitting the ‘ideal victim’ model.

As such, this trial is, fundamentally, a call to action. A warning that social media, no matter the platform or medium, cannot be trusted as an unbiased source of information – anti-Amber propaganda has been funded by right wing conservative media outlet, The Daily Wire, who spent tens of thousands of dollars promoting misleading news as Instagram and Facebook ads. Most critically, it’s a reminder to centre survivors, especially those around us, in the ways we navigate conversations of gendered violence.

By viewing cases such as this one through a trauma-informed lens, we acknowledge that one in three of us will experience domestic abuse or sexual violence in our lifetime. We remember, quite simply, that we never know what the person stood next to us has been through. And only by embodying compassion, empathy and collective care can we start to challenge the status quo from within our inner circles.

Abolishing gendered violence may seem like a mammoth task, but it doesn’t have to be. We don’t need to be activists or experts to do so. Sometimes the most meaningful change starts at home, on our social media feeds and in our WhatsApp groups. And I can guarantee the survivors you know will be grateful for your support.

As this is a deeply sensitive topic, comments are open to paid subscribers only. Thank you for your understanding.

Evie Muir is a domestic abuse specialist, racial justice activist and freelance journalist. With almost 10 years’ experience supporting survivors with intersecting experiences of gendered and racialised trauma, Evie now works with services committed to ensuring their practice is anti-racist and LGBT+ inclusive. A survivor herself, Evie seeks to platform the survivors’ voices too often marginalised from mainstream media. Evie is also the founder of Peaks of Colour, a Peak District-based walking club by and for people of colour, which explores the outdoors and the routes it offers to healing, recovery and justice. You can find her online, on Twitter, or on Instagram

The line ‘Johnny Depp and Amber Heard wouldn’t see what they said, I reasoned, but the survivors around them would.’ really stood out for me. It’s helped me see how damaging these memes and one liner ‘haha’ comments are, and to give public support, rather just private messages, is critical if we have any hope of changing the collective narrative.

Thanks for this article. I too have found the whole trial by social media and the level of hate around this trial deeply disturbing. It has been almost impossible to avoid but I can / we all can think carefully and choose how, and indeed whether, we respond to it.